- Wednesday 27th September Open 14.00 – 16.30

- Thursday 28th September MArch Inductions. Closed All Day.

- Friday 29th September Open from 11.30 – 16.30 (Lunch hour as normal 13.00-14.00)

- Thursday 5th October MA Inductions. Open from 12.00 – 16.30 (Lunch hour as normal 13.00-14.00)

- Friday 6th October BA Inductions. Closed All Day.

- Monday 9th October 3rd Year Intro. Open 09.30 – 15.00 (Lunch hour as normal 13.00-14.00)

- Wednesday 11th October First Year Intro. Open 10.30 – 16.30

Free Postage and Student discounts at 4D Modelshop for MSA Students

Hi all,

You may or may not be aware of the company 4D Modelshop who provide some of the materials and equipment we have here at the workshop and are usually present at any of our inductions.

As part of this years inductions they are offering some of our recommended basic tools and consumables at discounted prices and FREE postage to B.15 workshop on all orders made before 29th October.

- This applies to any items purchased from them not just the discounted recommended basic tools listed.

- In order to qualify for the free postage just add this B.15 link to your online shopping basket.

- In addition to the discounts on the basic tools you get a further 10% off anything as a student so don’t forget to register as an MSA Student and check ‘Student Account’ as you check out.

Once we receive any orders I’ll contact you via email.

Hope this is of some money saving use,

Scott

Welcome Back to 2017-18 at B.15

Welcome back to the new academic year!

Over the next few weeks things will be picking up starting with the induction of all newcomers in 1st year followed by some returning and some new students in 5th year MArch.

The dates for these are Tuesday 19th & Wednesday 20th September for BA inductions, Thursday 28th September for MArch. During these days access to all other years will be restricted.

What’s New at B.15 this year?

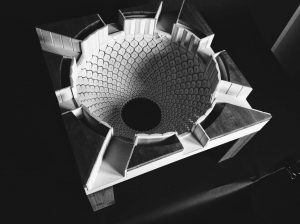

OBJET 30PRO 3D Printer

Over the summer we have installed a new type of 3D printer called a Stratasys Objet30Pro. This machine uses thin layers (28 microns) of resin to build objects which are supported by a jelly-like support material. Advantages of this machine are the fine layering which offers higher resolution prints, the ability to produce models in clear resin and the water soluble support material which is removed safely using a water jet system. Unfortunately this comes at a cost and the resin/support used is pricey indeed! It will be some time before the full extent of this machines capabilities are understood for our use so bare with us whilst we learn with you.

As with the other types of 3D printer the cost varies depending on the model. The exact cost in ml. of material to be confirmed but it’s likely to be the most expensive of the 3D printing options we have in B.15.

We intend to use this machine for specifically clear component requirements using Clear Resin called VeroClear. The outputs are clear but may require polishing to achieve a completely clear finish.

Reference Books

We have a few new additions to the B.15 reference Library as described below.

Model Perspectives: Structure, Architecture and Culture by Mark R. Cruvellier, Bjorn N. Sandaker and Luben Di, 2017

This brand new book presents a wide selection of case studies focussing in particular on structures and construction systems within building design. Each case study features a detailed overview essay and is accompanied by large prints of physical models that have been produced as part of each project. Some really great examples shown here – well worth a read.

supersurfaces: Folding as a method of generating forms for architecture, products and fashion by Sophia Vyzoviti, 2006

Folding Architecture: Spatial, Structural and Organizational Diagrams by Sophia Vyzoviti, 2003

Both of these pocket books by Sophia Vyzoviti provide a theoretical introduction to folding in design before presenting examples of folding techniques as the outputs of physical ‘paperfold’ algorithms. All featured work comes from within the context of architectural education and thus provides a great benchmark selection of works from you to take inspiration from. Great source material to get you started making sketch models.

Workshop Merchandise

We have recently had some workshop merchandise made up due to popular demand which is available to purchase in the workshop using the same payment system as the materials store.

Cotton Tote Bags with B.15 and new MSA branding and enamelled steel mugs (No drinking in the workshop people!) featuring the B.15 Logo are for sale both at £6 each with all money going straight back to the materials budget. There also is a T-shirt in development which we hope to have available soon. More information on that soon.

Materials Stock and Online Store Payments

There is no change to the payment system for materials and service payments this year. The full up to date materials list can be found here along with the link to the online store. We’d also like to remind everyone that payments should only be made after the materials have been issued to you as stock is variable and some items may not be available. Whilst we make an effort to keep things fully stocked at all times this is sometimes not possible therefore please remember that the materials list is a guide for your model design not a guarantee it is in stock all the time. Always come to the workshop and find either of us to enquire and make payments rather than making them from elsewhere.

Upcoming Exhibition

Following on from Atelier La Juntana Summer school back in July we hope to exhibit the work produced sometime in the coming months so look out for that happening. We’ll post updates regarding that on here and moodle.

Social media

If you haven’t already don’t forget to follow us on Instagram and Twitter @b15workshop where we regularly promote student work and ongoings in the workshop.

That’s all for now, See you soon!

Scott & Jim

Atelier La Juntana Summer School July 2017

Between 19th and 25th July a group of 14 MSA students and B.15 took part in ‘Modelmaking in the Digital Age’ Summer school in the North of Spain. Atelier La Juntana has been run for several years by Architect brothers Armor and Nertos Gutierrez Rivas along with their father, Daniel Gutierrez Adan. This is the first time the course has been held exclusively for a single institution.

The course is designed to encourage individuals to investigate different materials and processes and in turn open them up the possibilities within craft for their presentations. This is not a course about conclusions but about the journey of exploration and how we should each take more time to appreciate the hand crafted approach in our work.

Throughout the week students explored the following, each involving many sub processes:

Silicone Mould Making, Resin Casting, Jesmonite Casting, Casting with Pigments, Plaster Mould Making and Casting, Clay Tile Sculpting and Replication, Sand box Moulding, Casting Aluminium, Photo Etching on Zinc Plates, Hard Etching on Zinc Plates, Press Printing, Paper Embossing, Screen Making and Screen Printing on Fabrics.

All students took part in these activities getting to know much more about each process and it application as well as building great social links with each other. Outside of the workshop the group were taken on a tour of the surrounding area of the Liencres nature reserve and also of Santander. The tour took in the cities Cathedral and other architectural landmarks before visiting the ‘Arte Y Architecture’ exhibition which featured work from previous workshops.In addition to the practical tasks undertaken each day there were introductory lectures explaining each process and its application as well as a lecture from Croatian architect Rosa Rogina who presented some of her work which has used modelmaking to help convey important human messages looking at the rebuilding of a coral reef and also about the impact of land mines across former war zones.

The workshop culminated with a display of the outcomes from the across the week with each students explaining the process undertaken. Students were then given a diploma for their achievements before helping to put together a celebratory BBQ in the workshop garden.

We would like to thank everyone at Atelier La Juntana for making us all feel so welcome and putting on such a fantastic week for us all. In addition to that we would like to thank everybody who took part in this experience for making the trip over and getting involve. We hope everyone enjoyed it as much as we did and look forward to seeing the skills being used in your future projects!

We would like to thank everyone at Atelier La Juntana for making us all feel so welcome and putting on such a fantastic week for us all. In addition to that we would like to thank everybody who took part in this experience for making the trip over and getting involve. We hope everyone enjoyed it as much as we did and look forward to seeing the skills being used in your future projects!

It is hoped that the work will be put on display in the coming months here at Manchester School of Architecture and that Armor will be present to speak about the experience.

Look out for updates about this and future workshops! Find out more about Atelier La Juntana here.

Scott

Mecanoo B.15 Modelmaking Awards 2017 Winners

For the past three years Netherlands based architects Mecanoo have generously supported our desire to celebrate the use of models within architectural design. The awards consider not just a single piece of work but each individuals attitude and approach to using physical models as a vehicle to advance the understanding of their design to both themselves and to others.

After a very tough judging session this years Mecanoo B.15 modelmaking awards were announced on Friday evening at the official opening of the Manchester School of Architecture end of year show.

We can’t stress enough how worthy everyone who made the long and short lists were this year so everybody should be very proud of themselves for producing such a high standard of work across the board.

Judging was carried out by:

Mecanoo representatives Laurens Kistemaker, Oliver Boaler and Paul Thornber.

MSA lecturers Dr Ray Lucas and Amy Hanley.

B.15 Staff Jim Backhouse, Scott Miller and Phillipa Seagrave.

The full 2017 shortlist document can be downloaded by clicking here.

This years winners are:

MArch

MArch 1st Prize – James Donegan – Continuity in Architecture

MArch 2nd Prize – Samuel Stone – Continuity in Architecture

MArch 3rd Prize – Daniel Kirkby and Vanessa Torri – Urban Spatial Experimentation

BA Architecture

BA 1st Prize – Ghada Mudara – Urban Spatial Experimentation

BA 2nd Prize – Theodoris Tamvakis – QED

BA 3rd Prize – Arinjoy Sen – Common Ground

Mecanoo B.15 Modelmaking Awards 2017 Shortlist

In partnership with Mecanoo we are please to announce this years awards shortlist! This years work has been incredibly difficult to reduce down for this list and we at B.15 and Mecanoo want everyone to know how great the work has been. Well done all!

Final Judging will take place tomorrow (9/6/17) afternoon with the award winners being announced from 18.00 at the Exhibition opening. Good luck everyone!

The complete document can be downloaded here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0Byxdb-XNgTOtYlpjZWQtS2lSVTQ/view?usp=sharing

Easter Break and Late Opening Hours

Hi All,

The workshop will remain open for the first week of Easter break between 3rd and 7th April. We will then be closed until Monday 24th.

As previously announced there are 4 other mornings where we are closed after Easter: Wednesday 26th, Thursday 27th, Friday 28th April and Tuesday 2nd May – closed between 09.30 and 14.00.

Late opening hours

Beginning Monday 24th April the workshop will remain open for an extra 3 hours a day Monday to Thursday for 4 weeks. This includes the dates where we will be closed in the mornings mentioned above.

The workshop will remain open Monday -Thursday until 19.30 when students will be asked to clean up your workspace as normal in preparation for the following day. These temporary opening times are as follows:

Monday 09.30 – 19.30

Tuesday 09.30 – 19.30

Wednesday 09.30 – 19.30

Thursday 09.30 – 19.30

Friday 09.30 – 16.30

See you soon, Scott & Jim

Opening Hours Update

Hi All,

Reminder that there are a few dates over the next two months when the workshop will be closed for part or whole days. Take note to avoid disruption to your projects! Apologies for any inconvenience.

March

Friday 10th March – Closed between 11.30 – 14.00

Tuesday 14th March – Closed from 13.00 – 17.00

Friday 17th March – Closed All Day

Between 20th March and 31st March ‘Events’ projects are ongoing and will mean the workshop will be busier with booked events group’s taking priority to use the space.

April/May

Easter Opening and a period of Later opening hours will be confirmed soon in another post.

Wednesday 26th, Thursday 27th, Friday 28th April and Tuesday 2nd May – closed between 09.30 and 14.00. Open as normal each afternoon 14.00 – 16.30

Scott & Jim

Atelier La Juntana Summer School 2017 MSA Exclusive, Santander, Spain

We are pleased to announce an exclusive week long course of modelmaking and craft skills this summer taking place exclusively for MSA 2nd and 5th year students this July. This unique course takes place in a National Park in the North of Spain between 19th and 26th July 2017.

Atelier La Juntana is a week-long workshop experience designed to teach architecture students a wide range of traditional and contemporary skills for use in architectural modelmaking.

Watch the trailer for the school here:

This intensive course is designed to gives 15 students new skills and access to traditional and cutting edge facilities, allowing them to build on existing model making skills and raising the level significantly for future projects. The course is taught by Architects and Artists from the University of Madrid. B.15 technicians will also be attending alongside yourselves as participants in the course.

The cost of the course has been significantly subsidised for students of MSA to a cost of £354 per student (Correct as of March 5th 2017 -Subject to minor fluctuation in the exchange rate).

This cost covers the full 7 day course,accommodation for 8 nights (arriving Tuesday 18th July leaving 26th), The workshop is a full-time course, starting at 09.30am and finishing at 5.30pm each day, with a total of 56 learning hours. Each participant will have his or her own working space; access to Wi-Fi and the library, printer and plotter; a resting area in the garden; and access to a small kitchen.

Flights are the individuals responsibility to book. Direct flights to Santander or Bilbao (coach or train to Santander) can be booked from London – more information following application.

Deposits of 150 Euros each required by 14th April latest to secure accomodation and a place on the course. Remaining balance (subject to exchange rate) will need to be paid no later than June 15th.

Apply to Join!

What do you need to do to join us? The course is exclusively for 2nd and 5th year students wanting to pick up new skills to be brought back to the final year at MSA.

Please download and fill in the application document and return it as soon as possible to scott.miller@manchester.ac.uk

Due to the exclusivity of the course there are a limited number of places so please don’t hesitate to send your application over.

More information can be found on the official website here: http://www.atelierlajuntana.com/SummerWorkshop.html

If you have any questions please get in touch: scott.miller@manchester.ac.uk

We look forward to hearing for you!

Scott & Jim

Taking Making into Practice: Hawkins\Brown Architects

Earlier this year we were approached by Hawkins\Brown Architects to host a CPD session for their Manchester office, several of whom are Alumni of Manchester School of Architecture.

This gave us the opportunity to consolidate our current approach at MSA and present the idea of model making in a new inspirational light.

Much like our approach to tacking problems in the workshop we began by getting to the heart of the subject. Looking at the origins of the craft we asked ‘where did it all start and why?’ The craft’s background bares many similarities to our current thoughts and reasoning behind modelmaking. The physical model is viewed as an embodiment of ideas, beliefs and values to be read by others.

Our presentation followed the timeline of history, using ancient and classical precedents to modern day applications in architectural practice, portraying the changes for the maker and architect. Expanding on our exploration, we asked Hawkins\Brown to tell us their views from a project level and their thoughts on the future of modelmaking in practice. We gain an insight from Hawkins\Brown Architect and MSA Graduate Jack Stewart who has a keen interest in the ever evolving relationship between physical modelmaking and digital fabrication.

“I’d bet there isn’t a single project that makes it through Hawkins\Brown without at least one model being produced for it.

We can make models for all stages of projects and using models as design tools is an essential part of our process. Quick sketch models are invaluable to explore our ideas in three dimensions with design teams. Whilst these and more polished models are fantastic tools to help describe schemes to clients and sell schemes to stakeholders or consultation groups, such as planning. Clients love handling a tangible three dimensional object and we love testing them”

Education and Practice

The idea of making in practice is something that many of our students wish to continue and in many cases would gladly devote a lot of more of their time to. This often raises the question of how this ideology can be and is fulfilled in practice. What can come as a surprise is the broad selection of styles and scales of model making that is actively used in practice everyday.

For example Hawkins\Brown have just invested in a new modelmaking workshop space at their London base and have a designated maker space at their satellite Manchester office which recently celebrated its 1st year of work.

“Historically we have relied upon design teams to construct their own physical 3D models and when a particularly onerous or complex model has been required we would outsource this to a specialist model maker. We don’t anticipate the latter disappearing, but we do value the close link between our design teams and the models that they are using. As such we have recently employed an in-house model maker. We’re at a size now where an in-house model maker is really valuable to help educate on model making techniques, explore more possibilities, maintain the equipment that we have in-house and make the connection with external resources for machines and materials that we don’t have in-house. We anticipate this will help to take our in-house models to the next level.”

What is particularly encouraging about this approach is the value given to the craft of model making and the potential for those within architecture to utilise the skills they have learnt within their education.

“[Our] design process doesn’t follow a company standard. Every project is unique creating a unique series of design challenges. Like the adage says, ‘there are many ways to skin a cat’, it is up to the individuals within a design team to decide how they would like to best approach a design problem. In many cases this results in the creation of a physical model.”

Working space

Having worked in several different modelmaking companies and visited many different workshops, no two set-ups are the same. Finding a balance of the appropriate tools to fit out a workshop is instrumental in making each output achieve its intended purpose. Hawkins\Brown are striking this balance between hand craft and digital fabrication.

“We have much of the more traditional facilities and equipment such as cutting mats and tools for thinner sheet materials, hot wire cutters for foam models and numerous typical working tools for material preparation. We invested in a laser cutter four years ago, which further increased our ability for model production.”

The company have also recently purchased a ‘MakerBot’ and ProJet360 Powder printer with a view to speeding up the production of complex forms that can be deemed too time consuming for traditional making techniques during design development. Time, or a lack of it, is certainly a major consideration when it comes to the application of modelmaking in student submissions. The increased pressure for a variety of submissions at once allows little time to learn through making. This is something that we strive to improve upon, though how is this considered in practice? How does project time factor in allowance for modelmaking requirements? Jake Stephenson is a recent part 1 architect working at Hawkins\Brown who has continued modelmaking into practice.

“[Modelmaking] is very important and affirms what we learned at university about the process informing the design. In practice [modelmaking] goals are usually a decision made between myself and the project architect about when it would need to be completed by. Being realistic about my own time and skills as well as how fast a model would can be created. It’s very much about my awareness of time scales; booking laser cutting sessions, getting files ready – then allowing enough time to build my model for the deadline we set ourselves.

When it comes to costs it’s about giving options. For example when doing an iterative sketch model, I would use cheaper materials, compared to a model that is to show the client where the budget would generally be bigger for material costs. We would always try to source the cheapest most effective options by checking with multiple suppliers to get the most for our budget.”

Thoughts on the future

There are many perceptions of what it is to practice architecture as we are reminded daily in our workshop and without fail at every university open day. If we were to give a cross section of the questions we were regularly asked by prospective students and their parents it would invariably bring up something about technology and CAD driven machines. The awareness within the general public has increased due to the shift in accessibility of mainstream manufacturing techniques and prototyping. It’s important to remember that much of this stereolithographic technology is not as new as so often perceived. What has changed in recent years is the relative ease for interested parties to use it. This has led to an almost universal expectation that these mediums be made available in education and that accessing them is a given and large part of modern learning.

Our responses to the often broad enquiries in the area of 3D Printing and Laser cutting often lead us to ask a lot of ‘Why?’ based questions. ‘Why are we setting out to make a particular object and why do you believe such a machine can get you to that goal?’

Our concern and reasoning here is in the misuse of technology as a learning tool. There is often a strong desire from students to depend upon it without understanding their own intentions or purpose of their exploration through the model. We advocate the work ethos to our students to stop and think before diving straight in.

For Jack Stewart, having a strong interaction between traditional and contemporary data driven approaches is very important for successful outputs and effective learning within the Hawkins\Brown team.

“With BIM becoming ever more prevalent, in the construction industry, digital models for detail production and delivery of projects are becoming increasingly important. But how we generate the forms and arrangements of our buildings, at a concept design stage, benefits hugely from both digital and physical modelling too.

For CAD modelling it is a particularly interesting domain. A model that perhaps begins life as a simple massing study will evolve, through to construction, usually through numerous separated studies. However now, through using emerging generative modelling technology, this entire process can potentially be captured in one software tool. The possibilities here are that decisions made, that are dictating early design principles, could in theory be amended much later in the process with all subsequent detail updating accordingly. This is possible as more sophisticated digital models geometries can be defined as a series of design decisions that are stored as data, rather than statically sculpted ‘dumb objects’.

The benefits of models stored as data is the ability to translate this data, quite easily, into something else – something physical. And with the accessibility of rapid prototyping and the machines described previously the connection to and knowledge of these machines will likely become increasingly important. The techniques and skills needed for model making will certainly grow in this regard. Whilst the skill required to manually craft materials into beautiful models, should not be lost, I believe future model makers will become even more well versed in intelligently generating CAD models and then streamlining these for fabrication. Here I see the boundary that we define between digital and physical models, and between designer and model maker, changing.“

Putting together our initial presentation for a CPD has been a good opportunity to reflect and analyse our beliefs about modelmaking at B.15. With the ongoing digital shift in architecture, the role of the architect is changing and architectural education needs to respond to that. Graduates who can identify the best means to explore their ideas through proven skill will be more sought after than those who solely depend on technology to make their decisions. Our ongoing discussions with Hawkins\Brown have proved insightful and we look forward to working more with this growing practice.

Hawkins\Brown have offices in Manchester and London employing some 240 architects. Current projects include the London Crossrail development and the Schuster Annexe at The University of Manchester (render shown above).

Many Thanks to Jack Stewart & Harbinder Singh Birdi & to Laura Keay & Jake Stephenson for inviting us to present.

For More information visit: http://www.hawkinsbrown.com/

Scott Miller, B.15 Modelmaking Workshop 2017