There is very little published about the nearly lost art of cork modelling aside from a few fairly recent articles and research papers. Before being attributed to architectural forms in the 18th Century, carving with cork was a tradition associated with nativity scenes in southern Italy (Gillespie, 2017). The idea of modelling this way most likely came from a combination of convenience; cork being a common, lightweight and versatile material for quick fabrication, as much as any creative individuals desire to replicate and simply enjoy the tactile craft of making with it.

The refinement of this unusual but captivating form of modelling occurred during a great period of artistic and cultural exploration in Europe. During what could be described as the original ‘gap year’, eighteenth century grand touring took young people across the continent via the most notable and artistically rich cities. This was something of an exclusive privilege that required a significant wealth and strong will of curiosity for the unfamiliar. Everyday living requirements meant a need to be flexible in tastes both for practical and dietary comforts. On every level of perception the experience was sure to be eye opening for anyone willing to embark on such a journey.

Experiencing a new destination for the first time as a modern traveller, you would think it common place to see an abundance of stalls and shops stacked with keepsakes, often mass produced junk that are rife in tourist spots. At the time of the grand tours, this shameless ‘cashing-in’ trade was fledgling if non existent. Despite this, amongst the increasing number of visitors, there was a great desire to somehow record experiences of travelling which led to traditional and art’s and craft based methods or recording being adopted. Visitors fascinated by the large scale architecture and ruins of ancient Rome took time to draw, paint and carve what they saw in order to take some momentos home. This collective practice brought back a new vision, a blueprint of how the classical world could inform a modern British design.

- Fig.2 Hand Filing a Column from Cork ©Dieter Cöllen

- Fig.3 Cork Model of the Roman circular Temple of Vesta at Tivoli, a classical ruin which is said to have influenced Soanes designs for the Bank of England © Sir John Soane Museum, London

- Fig.4 Cork Model of the Temple of Zeus or Apollo (the so-called Temple of Neptune or Poseidon), Paestum Attributed to Domenico Padiglione c.1820 © Sir John Soane Museum, London

As well as the grand tourists giving these crafts a go themselves there were some forward thinking artisan-entrepreneurs who began producing models to sell. According to Dieter Cöllen the originator of this method of making is commonly thought to have been Roman architect Agusto Rosa. Following his death came Antonio Chichi who produced probably the most famous cork models for sale to tourists in Italy (Cöllen, 2014). These miniature 3D sketches, copies of the classics in that moment, would then find their way back over the Alps towards Western Europe and beyond with many ending up in private collections to this day.

Cöllen, an artist and craftsman, has become the current go-to maker on the subject of cork modelling or ‘Phelloplastike’ – a work derived from the Greek word for cork. His works have gained attention around the world for their outstanding levels of accuracy and due to the specialist nature of the medium it is widely thought that his skills and experience are unparalleled in the field. Whilst these works are undoubtedly stunning pieces many have had the advantage of modern crafts tools which puts the skill behind the original 18th Century examples into perspective.

Given the age of limited numbers of the surviving examples, careful conservation is essential to their preservation after many years in storage and a fluctuating relevance in society as they fell in and out of fashion. Conservator Sarah Babister states that cork models ‘were really popular at a certain time and were kept as tools to teach students. Then they fell out of fashion and a lot of them were disposed of.’ (Kate C. 2014).

This helps to explain why there are so few examples surviving on public display. There has however been a recent recognition of the value of cork models which has led to a more conscious conservation of these pieces with the excellent reinstatement of the Soane model room and a fantastic Colosseum at Australia’s Museum Victoria.

This original 18th century model (Fig.5) was produced by British modelmaker Richard Du Bourg and thankfully spared the ‘no longer in vogue’ fate of so many of his other works. Richard Gillespie at Museum Victoria has written on the subject that stemmed from his intrigue of the Colosseum model that had sat unused in the museum stores for some 20 years. Having researched and discovered several other examples of Cork Colosseum models in European collections Gillespie concludes that separately these models had varied purposes. This is reflective of the wider, multifaceted use of modelmaking in architecture in contemporary practice.

“The [various] Colosseum models […] differed in purpose, combining to different degrees antiquarian interest, archaeological research and documentation, evocation of classical architecture and history, courtly collections, public exhibition and education, commercial opportunity – and artistic endeavour, for the carving of cork into extraordinary classical structures and architecture had a technical and aesthetic appeal for the modellers and their audiences” (Gillespie, 2016)

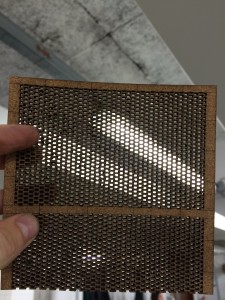

- Fig 6. Cork Block and Sheet

- Fig 7. A cork sketch model by the author.

Using Cork Modelling Today

In current practice cork is still used on occasion by modelmakers but rarely as the sole building material as it was in the golden age of the grand tourist. Makers wanting to try their hand today can find cork in good art and craft stores in both thin sheet and block form. In sheet form it has proved popular and lends itself well to the 21st century workhorse of the workshop, the laser cutter. Over the last few years we have moved to encourage aspects of this classical method of making into some of our works here at B.15. Using files, scalpels and sandpaper it is easy and engaging to sculpt into pieces of cork often requiring the user to study the subject in greater detail than they might on passing, much like life drawing or sketching.

I recently ran a short workshop on sculpting in cork in association with the ‘What We Do Here’ film project at the European Cultural Centre in Venice during the 16th Architecture Biennale. The atelier symposium; ‘Joined Up Thinking’ presented different approaches to studying, recording and designing space. Students of MSA’s Platform Atelier were given blocks of cork with the task of recreating a detail chosen from their time exploring Venice. These sketch models allowed students to engage with the material, largely for the first time, and to think about their chosen subject in carefully considered stages due to the subtractive process.

Senior lecturer and head of Platform atelier Matt Ault explains the context of the task in his teaching:

“The ever increasing availability and access to computational power continues to expand our design capacity for conceptualising, developing, communicating and fabricating. The move towards digital craft and digital tectonics recognises the central role of materiality and materialisation in architectural design and allows the benefits of the digital to be informed by our own material understanding.

Active sketching techniques of drawing, modelling and making result in a deeper understanding of any idea under interrogation or critique.

Our recent use of the cork sketching technique in Venice is part of a design task that also comprises the complimentary techniques in modelling and fabrication: digitally exploring complex, fluid surface morphologies by defining associative geometries that can be manipulated on screen. Design iterations can be quickly and cheaply made physical through manufacturing and assembling from paper or card with the digital plotter-cutter. Testing, evaluation and understanding of the material sketch model and its construction logic feeds back into the digital modelling to evolve the design.”

- Fig 8. Cork sketch modelmaking ‘Grand Tour’ task with MSA Platform Atelier

- Fig 9. Cork sketch modelmaking ‘Grand Tour’ task with MSA Platform Atelier

- Fig 10. Sketch model blocks from the ‘Grand Tour’ task with MSA’s Platform Atelier

- Fig 11. A happy group following their cork making task in Venice

Despite its age as a modelling method, it was clear following this task that cork sculpting can still offer us a mode of thought that the most contemporary mediums often steer us away from. It provides a much needed tactility to students learning along with the opportunity to expand on unknown possibilities that result from “mistakes” made along the way. During the assignment the concentration in the room was palpable with everyone, tutors included absorbed in the task at hand whilst clearly enjoying the process.

The work produced, along with additional cork sketch models will be featured at the MSA end of year show presenting the cork sculpts as 3D sketches. I look forward to seeing more examples in the coming weeks.

Scott Miller 2019

References

Ault, M, 2019, Cork Task [E-Mail]

C. Kate, 2014. Cork Colosseum X-Ray [Online Article] Available From: http://museumvictoria.com.au/about/mv-blog/apr-2014/cork-colosseum-x-ray/ Accessed 01/12/2014

Coffin, S. D. 2014. Cork for More Than Wine, The Temple of Vesta, Tivoli [Online Article] http://www.cooperhewitt.org/2014/10/30/cork-for-more-than-wine-the-temple-of-vesta-tivoli/ Accessed 01/12/14

Collen, D. 2013. The Cork-Models [Online Article] Available from: http://www.coellen-cork.com/eng/antike/history.htm Accessed 01/12/2014

Fouskaris, J. 2006. Studio I – Music Stroll Garden [Online Article] Available From: http://www.jonfouskaris.com/portfolio/music-garden.html Accessed 01/12/2014

Gillespie, R. 2016. Journal of the Classical Association of Victoria, New Series, Volume 29, From ‘Trash’ to Treasure: Museum Victoria’s Colosseum Model Available from: https://classicsvic.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/gillespie.pdf Accessed 26/11/2018

Gillespie, R. 2017. Journal of the History of Collections vol. 29 no. 2 pp. 251–269, Richard Du Bourg’s ‘Classical Exhibition’ Available From: https://academic.oup.com/jhc/article-abstract/29/2/251/2503305

Mass, M. 2014. Rare Model Craft: In The Beginning There was The Cork [Online Article] Available From: http://www.spiegel.de/karriere/berufsleben/kork-modelle-von-antiken-bauwerken-dieter-coellen-baut-miniaturen-a-983770.html Accessed 01/12/2014

Images

Fig. 1: Coellen, D. 2013 Tempel des Castor und Pollux [Online Image] Available from: http://www.spiegel.de/fotostrecke/dieter-coellen-baut-korkmodelle-von-antiken-bauwerken-fotostrecke-115570-8.html Accessed 01/12/2014

Fig. 2: Coellen, D. 2013 Natur pur (2) [Online Image] Available From: http://www.spiegel.de/fotostrecke/dieter-coellen-baut-korkmodelle-von-antiken-bauwerken-fotostrecke-115570-3 Accessed 01/12/2014

Fig 3. Sir John Soanes Museum, London, Model of the Roman circular Temple of Vesta at Tivoli, near Rome, by Giovanni Altieri [Online Image]Available From: http://collections.soane.org/object-mr2 Accessed 01/10/2018

Fig 4. Sir John Soanes Museum, London, Model of the Temple of Zeus or Apollo (the so-called Temple of Neptune or Poseidon), Paestum Attributed to Domenico Padiglione c.1820 [Online Image]Available From: http://collections.soane.org/object-mr25 Accessed 01/10/2018

Fig 5. Museums Victoria Collections, Melbourne Australia, Model – Colosseum, Richard Du Bourg, London 1775 [Online Image] Available From: https://collections.museumvictoria.com.au/items/715107 Accessed 27/11/2018

Fig 6. Miller S. 2015, Cork Block and Sheet [Original Image]

Fig 7. Miller S. 2015, A cork sketch model by the author. [Original Image]

Figs 8 – 11. Miller S. 2018 ‘Grand Tour’ cork modelling task in Venice in association with the ECC [Original Images]