5th Year MA student Daniel Kempski came to the workshop fairly late on in his project with a need to convey multiple aspects of his design proposals through model making. Having successfully completed his two projects and some valuble lessons learnt. Of particular note was the time consuming engraving and cutting of the cork elements. The results of this were fantastic but it should be noted that this can be very time consuming and therefore potentially costly in terms of laser cutting time. We asked if Daniel would write us a piece to accompany some images of his models – he responded in great detail!

We look forward to seeing some more of Daniels projects next year.

The full description of the project and the application of the models made with us is explained here:

“The culture of use:reuse within the construction industry is an emerging area of importance within the field – with firms being placed under increasing scrutiny to change their methods building demolition and deconstruction in order to evolve to meet the growing demands of waste management. It is key to address this issue parallel to the growing dereliction within our cities – with many buildings being demolished once being deemed unusable.

How this can be linked to programme arrives through the notion of an Urban Auction House: a place where individuals can bring their waste materials (arriving as deconstructed elements) and then be further sold to buyers who can make use of these products.

The scheme acts as a hub for all types of individuals within the construction industry. It tries to establish an even playing field for its users, with products being available at a reduced price due to their imperfect nature – enabling the customer to be able to purchase construction materials at a cheaper rate, seeking to reduce the current gap between small and large scale developers within the market.

The aim of the design is to maximise retention of the existing building (Albert Warehouse), while not constraining myself to remain within the existing structures parameters and potentially harming the programmatic outputs. I aimed to change and manipulate these aspects of the existing form that I felt did not fulfil its true architectural potential.

An entire new central bay is established between two existing segments of the build – enabling a more focused entrance point to be generated – recessed back from the roadside, with an element of grandeur created through the staggered, vaulted stonework.

I feel it was key to investigate the building in two different scale models: a 1:100 Section through the scheme in order to understand the internal workings programmatically; and a 1:50 Bay Study to investigate the materiality and light qualities.

1:100 Model

One of the more demanding changes to the existing structure arrives in the form of the central bay being deconstructed and replaced by a primary structure primarily formed by reclaimed stonework sourced from Quay House (one of the four Urban Mines). It was vital to interject a new, more accessible entrance to the building for the main visitors entrance in order to establish a focal point for the east facade (for sake of both functionality and aesthetics).

Recessing the entrance away from the pavement provides a much needed forecourt, reinforcing this new change of threshold through vaulted stonework encapsulating the individual as they proceed to enter the Auction House.

The Auction Hall is embodied within a double-height space, overlooking the River Irwell – creating the sense of theatre to be instilled upon the individual, with grand, exposed structure and a resonating acoustic acting as key protagonists. A raised platform further enables individuals to spectate during the auctions.

In contrast, the Lower Ground Floor functions as a back-of-house storage and preparation area. The workers gather and move the materials during their journey within the Auction House.

1:50 Model

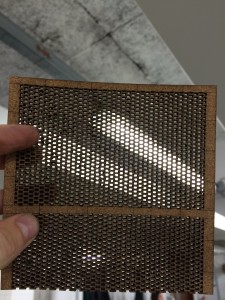

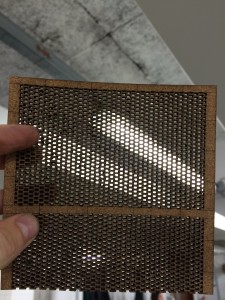

In order to gain a practical understanding of the atmosphere generated by the materials reprogrammed into southern elevation’s perforated brickwork facade,a scaled 1:50 model was constructed. The aim of the model was to investigate the internal light qualities predominantly, to ensure that the transitional space could not be deemed unwelcoming.

The model was also generated to create a built example of a key bay detail that repeats several times along that facade. The proportion between punctured brickwork and the actual structural masonry is key to enable the maximum introduction of natural light, while retaining structural integrity. The light qualities within the transitional spaces are key towards ensuring the success of the internal programme of the building – circulation spaces are there to offer relief in order to create a sense of separation between the Auction House and Galleries.

The large, double height spaces allow natural light to arrive from both the VSCs and punctured brick facade, allowing the central exhibition pieces to have their qualities maximised, as well as the space itself.

Making the Models

It was key to establish distinguishing characteristics between each of the materials used, as the scheme revolves purely around material reclamation (both architecturally and programmatically) It was vital to represent materials under same semantic in the building specification, as the same material choice in the model – enabling an easy understanding of the intended material discourse: e.g. obvious differentiation between stonework, timber, masonry, etc.

I felt it was key not to oversaturate the models with materials, instead working with three or four strong materials that work complementary to each other provided end products that felt cohesive.

Within the 1:100 sectional model it was key to establish a strong juxtaposition of materials in order to depict what elements of the build are retained and newly interjected. This is attempted by utilising 3D printed elements to narrate the qualities of the proposed stonework bay, with the etched 3mm plywood representing part of the retained masonry bay.

For the 1:50 bay study, 3mm cork board was used as the primary component to replicate the texture and ultimate aesthetic of the masonry – this was to ensure that minimal finishes had to be applied to the already delicate nature of the perforation post-cutting, providing the facade with a more natural demeanour.

Plaster-casts were made in order to distinguish a level of material separation within the space – focusing primarily between what is stonework and what is masonry. Both materials are reused, as recognised within the programme of the build, and thus is was key to attempt to create a more textured, used finish – achieved by placing a larger build-up of petroleum jelly within the moulds, creating a more textured finish.

Through the process of making both of these models, I feel that a greater understanding has been generated towards the atmosphere created within a building through the interrelationship of materials used within. It is far too easy to remain focused upon the external qualities of a site – and have that overshadow the internal conditions.

Combining both digital fabrication and hand crafted elements provides the ability to work efficiently and precisely, without generating a too-clean portrayal of the scheme. Regardless of the desired atmosphere within the build, I feel it is key to always develop your model-making understanding and techniques; with many components that could be made incredibly easily by hand, are now subject to digital methods due to sake of ease.”